The Island Dump: An Elegy

On an early morning last fall, one of the two attendants at the Vinalhaven Landfill and Transfer Station arrived to find that a raccoon had climbed into the big trash compactor and couldn’t get out. The attendant retrieved a gaff he kept handy for just this purpose, propped it up inside the container, then halted operations and removed himself and others to a discreet distance so as not to embarrass the little fellow when he scurried sheepishly up the pole and ran off into the bushes.

Although it’s truly a waste management facility, the Vinalhaven Landfill is often referred to, particularly by those of us with a long memory, as The Dump. And the humane and context-sensitive approach the attendant used that morning is consistent with our island dump and the role it plays in our community.

Like towns elsewhere, our island dumps were once plentiful—a historic component and consequence of colonization. During the first 100 years or so, they were created, nourished by, and served a particular homestead, often a farm. But as roads and the means of getting around improved, common areas were found—places where trash, hauled from surrounding households or businesses, could be dumped in one place. This also meant that the more-concentrated population of rats and similarly incidental critters could be more readily managed (i.e., shot, poisoned, or otherwise set upon).

The nondegradable residuals of these common areas, created where a property owner was found to be agreeable—or maybe just absent, or offering little or no resistance—can still be found here and there with a cursory examination of the island’s interior or shoreline.

By the early 1900s, the number of community dumps on Vinalhaven had dwindled considerably. Two major sites served most islanders, who by then lived around Carver’s Harbor and the island’s southern extremities.

Man-made land, created from what is known locally as grout—the fill that was a by-product of the island’s granite quarrying—had not long before become Main Street, bridging the gap between those living on the west side of Carver’s Harbor and those living on the east. While it afforded, at long last, easy intermingling and commerce, it had not quite erased the distinction relished by the two respective populations. Those who lived on either side referred, with genial derision, to those on the opposite shore as “Over-Crossters,” a shortened version of “over across on the other side,” and, as late as the mid-1940s, each side retained a proprietary attitude toward their respective garbage. Those on the west dumped off a high cliff up on Skin Hill, where it accumulated in a pile on the southeast side of Sand’s Quarry. We on the east took ours to a site down at East Boston, where we flung it cavalierly from a pile of grout onto the shore and into the waters on the east side of Indian Creek.

In either case, we chucked whatever we didn’t burn or compost: bottom paint, waste oil, old cars (or car parts and broken engines), house paint, batteries, medical waste, fish carcasses, solvents, the stuff from the outhouse, dead animals, worn-out bait bags, radio tubes, glass bottles, tin cans, and so forth, and with it all went xylene, arsenic, chloroform, mercury, lead, vinyl chloride, and other goodies.

On Skin Hill, it went over the side for decades to leach happily into or simply combine with the water in the quarry, a common swimming hole. Over at East Boston it introduced an unwanted element into the environment, and into the embryonic development of larvae that came ashore to molt into miniature lobsters.

In the mid-1940s, the private property owners who for so long had essentially hosted municipal disposal began resisting. Perhaps they were ahead of their time and more aware of the consequences than everyone else. Perhaps they simply thought it unsightly. At any rate, the town found it necessary to provide a centralized and sanctioned place where we could all take our trash, and so designated some town land on the east side in Roberts Harbor and just opposite Narrows Island as “The Dump.” It also happened to be abreast of a popular and productive clamming site. At the time, having simply declared the site to be “The Dump” was sufficient, for there was no oversight, no attendant, and no limit to what could be disposed of there.

A favorite activity of many at the time, myself included, was to sit on your tailgate with a Haffenreffer beer in one hand and a .22 in the other, shooting rats for the better part of an evening. The vast number of those creatures is one of the few phenomena from that period that still remains intact and unfettered in my memory.

In the mid-1960s, environmental awareness became manifest, if only dimly. Folks were still routinely taking trash into town on the way to the store or the post office and throwing it over the bridge as they went by, and were then offended and angered when taken to task for it. The evidence of the damage the shorefront dump was having on the surroundings (clams couldn’t be harvested anywhere near the site) could no longer be denied, or ignored. The town bit the bullet and moved The Dump to an inland site on land donated to us for just that purpose.

Although it was no longer near the shore, The Dump was now situated in a significant wetland and recharge area, and was otherwise pretty much what it had always been, with no controls, no limitations, and no oversight except for a hand-lettered notice painted on a piece of plywood nailed to a tree that read dump on the other side of the log. And except for having someone come in once in a while to push stuff farther off with a bulldozer, young men and boys still went up at night and settled in to drink beer and shoot rats.

By the late 1990s, most of us were reconciled to the fact that as a species, we had done a lot of harm to our surroundings. The state compelled the town to take meaningful and fairly drastic action to rein in what was a toxic and spreading quagmire that was leaking an unappealing leachate into surrounding wetlands, endangering wells and homes and, most significantly, our sole-source aquifer.

A landfill committee was formed. The Dump was closed to further disposal, open-top trailers were installed at the site, a bag fee imposed, and, while the thoughtful members of the committee considered the parameters of compliance with State Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) directives, all of the island’s trash was trucked off-island, often daily, to collection facilities on the mainland.

At the time, the DEP routinely mandated that municipal dumps, those to be closed and the land reclaimed, be covered first with a vented geocomposite liner, then with six feet of a particular sand, and, finally, with a significant layer of clay or loam laid over the entire area. Since Vinalhaven had no clay or loam in significant amounts, the committee suggested to the DEP that we be allowed to use granite; that we install a crusher at one of the town’s huge and ubiquitous piles of residual grout (the same stuff that Main Street was created from); and that we truck it to the landfill for cover.

The DEP denied our request.

We persisted, created a test area, and demonstrated the utility of using crushed stone. While we persisted, resistance to fees waned and enthusiasm and support for the project grew.

Eventually, after two long years of persuasive arguing, the DEP relented, but by then State financing for such projects was running out, and not likely to be re-funded. Legislative testimony from Sue Lessard, our town manager at the time, persuaded the State that the town could not foot the bill for this reclamation on its own, and would suffer immeasurably if the town’s main harbor were taken over by barges, each carrying the mandated material, arriving all day, every day, for a year or more, displacing dozens of lobstermen and buying stations.

The State was persuaded to provide 75 percent of the funding themselves, and we, the remaining 25 percent. The finished project—the only reclaimed dump in Maine to have been covered with crushed stone—was given an award for utility and aesthetics by the state. Tellingly, not a single rat has been sighted in the area in the 13 years since the project was completed.

Over the next few years, our waste management became a reality. Sorting stations now distinguish one recyclable material from another; an area has been created where legitimately burnable materials can now and then safely be turned into a conflagration; hazardous items are sorted and collected separately; construction debris is monitored and collected; and the entire assortment is trucked off the island as and when required.

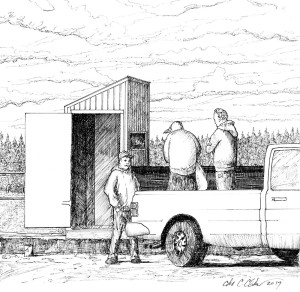

Finally, and of greater significance, the opportunity to sift through discarded material to find something useful is afforded not only by a remarkably well-provisioned and continually refreshed Swap Shop, including a tidy shelter for electronics and another for paint, but also by the exceeding willingness of the two very congenial and patient attendants who oversee this considerable operation. Kenny and Luther go out of their way to make those things readily apparent and accessible—even keeping tabs on who needs what, and setting those things aside when and if they appear.

While some folks only visit The Dump so they can appreciate the magnificent bottle collection the two maintain in their office, homes are also furnished, lives begun and discarded, deals consummated, problems solved, acquaintances made and remade, and assistance sought and found. A great deal is accomplished at The Dump, much of it made possible by Luther and Kenny, public servants in the truest sense of the word.

Today, the rats are mostly gone. Visiting critters now are more likely to be seagulls or the occasional raccoon. And instead of .22 bullets, it’s a helpful hand out of a soon-to-be-tight place they are offered. There’s no bottom paint spilled on the ground, no soiled diapers open to the sun. But the archaeologists will have the last word, digging and sifting out the granite tailings and examining what we 20th-century islanders deemed worthless.